The third Monday in January is a U.S. federal holiday honoring the late civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., but two Southern states — Alabama and Mississippi — also use the day to celebrate Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate forces during the Civil War.

Public interest lawyer Bryan Stevenson lives in Alabama and is the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, which works to combat injustice in the U.S. legal system. The new movie, Just Mercy, is an adaptation of his 2014 memoir of the same name. He says that the fact that his state honors Lee at all — let alone on the same day as King — is a sign that America has not acknowledged the evils of its past.

"In the American South, where I live, the landscape is littered with the iconography of the Confederacy," Stevenson says. "We actually celebrate the architects and defenders of enslavement. For me, that has to change if we're going to get to the kind of healthy place I think we need to get to."

Stevenson has traveled the world, observing how other cultures address the injustices of the past. He notes that Johannesburg has a museum and monuments that "talk about the wrongfulness of apartheid." In Berlin, he says, "You can't go 200 meters without seeing markers and stones placed next to the homes of Jewish families that were abducted during the Holocaust."

"But in this country," he says, "we don't have institutions that are dedicated and focused to making sure a new generation of Americans appreciates the wrongfulness of what we did when we allowed lynching to prevail and persist, what we did when we created racial apartheid through segregation."

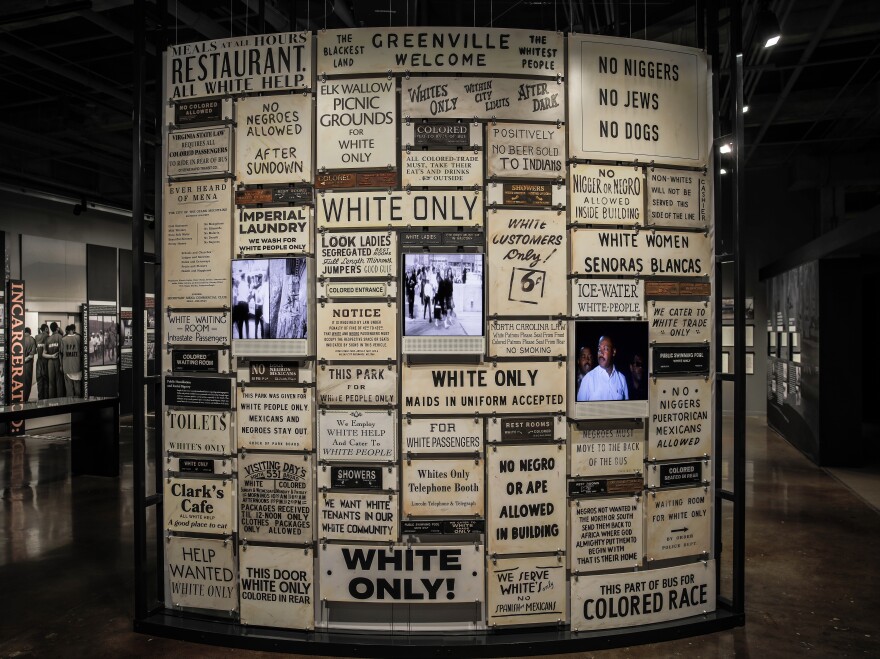

In 2018, Stevenson and his organization opened the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., both dedicated to the legacy of slavery, lynching, segregation and mass incarceration in the U.S. For Stevenson, the museum and the monument are an effort to address the past — and to change the future.

"I just felt like we had to introduce a narrative about American history that wasn't [being] clearly articulated," he says. "We need to create institutions in this country that motivate more people to say 'Never again' to racial bias and bigotry."

Interview highlights

On the "great evil" of slavery in America

The great evil of American slavery wasn't involuntary servitude. It wasn't forced labor. It was this idea, this narrative, that black people aren't as good as white people, that black people aren't fully human. [That] black people aren't evolved. [That] they can't do this, they can't do that. And that narrative created an ideology of white supremacy. And for me, that was the true evil of American slavery.

After the Civil War, there were 100 years of terrorism and violence. Black people were pulled out of their homes, beaten, drowned, burned, tortured and lynched. And the law did nothing. Communities did nothing. The nation did nothing.

We passed the 13th Amendment that prohibits involuntary servitude, enforced labor, but it doesn't say anything about ending this narrative of racial difference, and because of that, I don't think slavery ended in 1865. I think it evolved. And this wasn't a narrative we had actually articulated.

After the Civil War, there were 100 years of terrorism and violence. Black people were pulled out of their homes, beaten, drowned, burned, tortured and lynched. And the law did nothing. Communities did nothing. The nation did nothing. And then when we got to the civil rights movement, we had this heroic moment. But that narrative of racial difference, this presumption of dangerousness and guilt continued past that era — and we're still burdened with it today.

On the Legacy Museum

It's located in a building that is the former site where a slave warehouse existed. And we want people to know that they're standing on ground where enslaved people were put in pens and held. It's a block from the auction space where enslaved people were taken to the square and sold. And it's a first-person experience. We actually went through hundreds of slave narratives and took these accounts, which are heartbreaking and devastating, and you come in and you see the visuals that you would see if you were enslaved going into a dark dungeon-like space. We have these pens that are slave pens and they look empty. But when you walk up to them, it triggers a motion sensor and a hologram will appear and you'll see and hear an enslaved person who will give an account of how they were pulled away from their siblings, their parents, their children, how they were sold. And getting people closer to the anguish and the suffering is part of what we're trying to do.

On what EJI's research about lynching revealed

During our research, we were able to document about 800 more lynchings than had previously been documented. And I think what emerged to me that was really heartbreaking is that so many people were lynched just because they wanted to be free. Mary Turner was lynched in Georgia because she complained about the fact that her husband had been lynched. Elizabeth Lawrence was lynched in Birmingham, Ala., because she told schoolchildren who were throwing rocks at her that they shouldn't do that, and because she had the audacity as a black woman to scold these white kids, a mob formed and they came to her home and they lynched her.

Black people were lynched because they wanted better pay as sharecroppers, as tenant farmers because they tried to organize things. Preachers were lynched because they talked about freedom. People were lynched sometimes because they didn't call a white man, "sir," because they didn't get off the sidewalk when white people walked past. And it caused me to appreciate the absolute terror of living in a place where the most insignificant encounter might turn into an incident where you or your loved one could be killed. And that's the trauma. That's the weight that this history created that I don't think many people appreciate.

On the connection between the death penalty and lynching

Most people don't appreciate that the most violent time for black people in American history was in the first weeks and months at the end of the Civil War. Yes, it's only in the late 19th century and 20th century that legalized killing takes on the prominence that it does, and as we start limiting these mob killings through lynching in the '30s and '40s, you begin to see the modern death penalty begin. ... Between 1930 and 1972, the rate of execution skyrockets. And there you begin to see black people being executed rather than lynched, but [the death penalty is] not any more reliable. It's almost like they went from outdoor lynchings to indoor executions, and the error rate is incredibly high.

On how he processes the anger he feels about his family's history (his great-grandfather was enslaved, his grandfather was murdered and the injustices he sees every day in his work

I've always understood that anger, as an end, doesn't achieve anything. I guess in some ways I'm tired of just being emotional about this history. I want things to change. I want to see real change. And I represent people who are so much more vulnerable than I am. That's the thing about my work that allows me to put in context my own emotions. I go into jails and prisons. I stand next to condemned people who are facing execution. I spend time with mothers whose children have been taken away and condemned to die in prison. I've been next to kids who've been abused in jails and prisons, who are being threatened. And when you're working with a population like that, who is so vulnerable, you have to be willing to figure out a way to help them, and you can't let your emotions be the end of the story. ...

I've always understood that anger, as an end, doesn't achieve anything.

I have to believe things I haven't seen. We couldn't have gotten 140 people off death row if I wasn't willing to believe something I hadn't seen. We couldn't build this museum or this memorial if we weren't willing to believe things we haven't seen. I went to Harvard Law School — I'd never met a lawyer until I got to law school. And I just think that has to be the orientation that sustains and defines what we do. It can't end with anger. It can't end with fear. We get to a better place, we get to justice, when we get past fear and anger.

Roberta Shorrock and Seth Kelley produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.