Tennessee ranks in the bottom half of U.S. states for child welfare, according to new research from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Tennessee’s rank of 36 is the same position as last year.

The report’s data on Tennessee children’s health, including low birth weight, obesity and child and teen deaths, as well as measures of education, including young children not in school, and reading and math proficiency, all worsened since the last report. Tennessee ranks 41 for children’s health.

One brighter spot in the report was a decrease in children living in poverty from 2019 to 2021, with a significant drop in high-poverty areas. About one in six Tennessee children lives in poverty, just above the national average.

“It’s still a little high, but it’s the best number that we’ve had,” said Rose Naccarato, director of data and communication for the Tennessee Commission on Children and Youth. “So maybe some of the focus on bringing business to rural areas has helped increase the number of children who have risen out of poverty in those areas. It’s hard to tie these results back to particular policies, but that may have contributed.”

There were increases, however, in child and teen deaths in the state from 32 to 40 per 100,000 from 2019 to 2021. Tennessee also had worsening educational outcomes, with 70% of fourth-graders considered “not proficient” in reading. Eighth-graders also saw an increase in those not proficient in math from 69% in 2019 to 75% in 2021, only slightly above the national average at 74%.

“One of the things that caused us to take a little drop in education was the fourth-grade reading scores where the rank fell during COVID,” Naccarato said in an interview. “That test they give that drives that measure is only given every two years and since it was last given, Tennessee has had another set of TCAPS and has shown a lot of improvements in reading. So, I think that’s going to come back up some on its own.”

Many of the child welfare indicators differ widely when race becomes a factor, with Black and Latino children often faring worse than their white counterparts. Over a quarter of all Black and Latino children live in poverty compared to 13% of white children. The death rate among Black children and teens is 73 per 100,000.

About 26% of children live in households with a high housing cost burden, and 30% of children are living with parents who lack secure employment.

“We are keenly aware of the high housing burden that folks that are particularly living in the urban parts of the state are experiencing,” said Richard Kennedy, executive director for the Tennessee Commission on Children and Youth. “I think that this continues to show us that we have opportunities with housing space to really be able to develop strategies to be able to have more affordable housing as part of a community housing plan to be able to reduce some of that cost.”

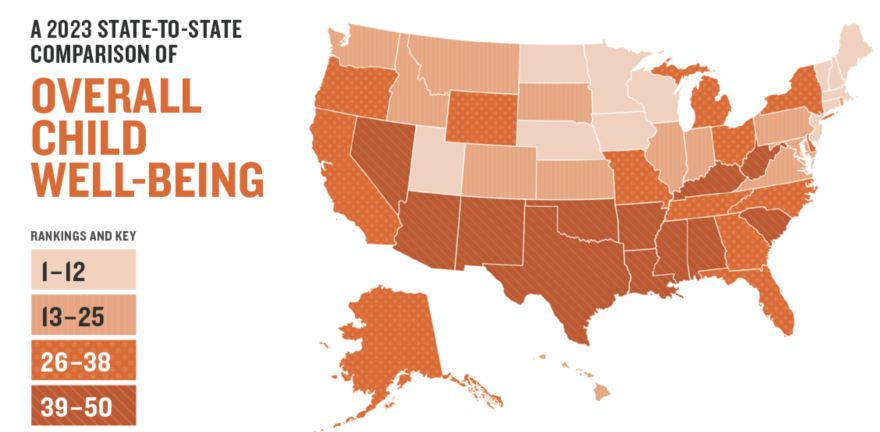

Appalachian states as well as states in the Southwest and Southeast consistently ranked the lowest. The 15 lowest-ranked states are in these areas, not counting Alaska, which also ranked low.

The focus of the Annie E. Casey Foundation this year was the affordability of childcare. On average in Tennessee, childcare for toddlers was around $7,300 or around 8% of the medium income of a married couple and 27% for single mothers.

“(The Department of Human Services) is doing some really interesting work that is looking at giving additional dollars towards rate increases but also looking at what are some unique public private partnership types of strategies that businesses and communities can engage in to be able to address those childcare deserts and the cost,” Kennedy said.

One such public-private partnership was announced by Tyson Foods last year at its Humboldt, Tennessee, plant, where it opened a $3.5 million childcare facility to accommodate up to 100 children who are 5 or younger.

“I think there is also room for conversations looking at micro-sites or some extended family sites that could allow folks that care for a fewer number of children to maybe have some different license standards as well,” Kennedy said. “So, I think there are some creative policy mechanisms as well as some community public-private partnerships that can be put into place to help to continue to solve the issue.”