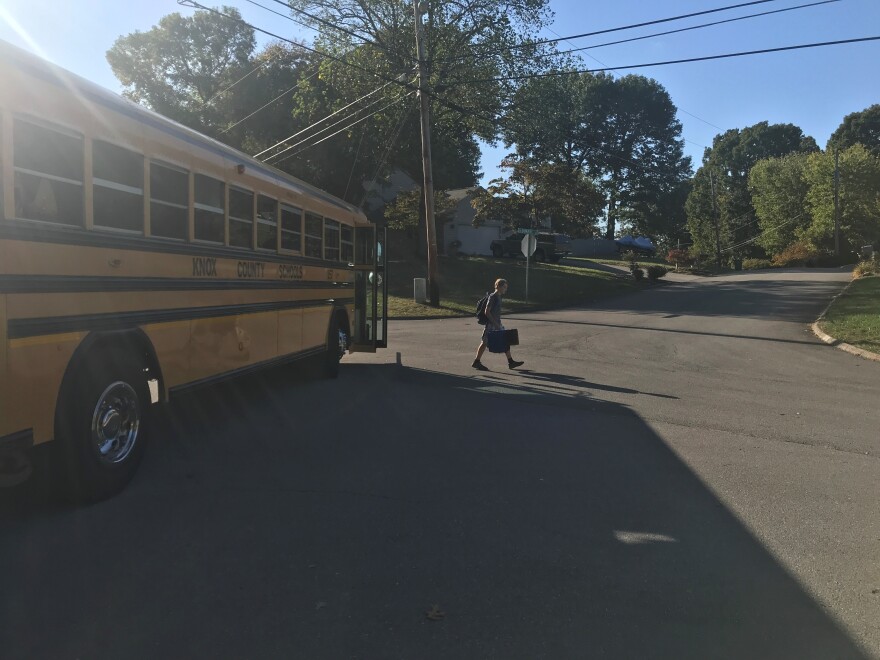

Sixth-grader Hunter Simmons lives just two and a half miles from West Valley Middle School, but it takes him more than an hour to get home by bus. That’s because his bus route still has no regular bus and driver, even though a quarter of the school year is already over. Other buses pick up the kids from his neighborhood after running another route.

Hunter makes the best of the situation, which gives him extra time to practice his trumpet with friends after school. But sometimes getting home shortly before 5 p.m. makes him late for activities, like Boy Scouts, and leaves less time for homework.

“I get home really late, and if we have a lot of homework we can get some done at school, and some hard problems we need to do we can do home when it’s quiet,” he said. “Because in bus hall it’s really loud.”

The situation isn’t what school transportation officials want. Hunter’s is one of five bus routes that get picked up and dropped off as a second load. That’s down from 10 at the beginning of the school year.

“It’s not great,” said transportation director Ryan Dillingham. “But it is not as bad as it has been in the past. And we have drivers in the pipeline now, which is not something we’ve been able to say over the past few years. So I am confident we’re moving in the right direction.”

A survey by the industry magazine School Bus Fleet found 90 percent of the nation’s school districts have a bus driver shortage. Almost a third called it “severe” or “desperate.” Tennessee raised its legal bus driving age from 21 to 25 last year, further shrinking the pool of eligible drivers.

For a while, the Knox County school district was losing drivers to neighboring districts that paid better. In 2016, the county school board approved three years of $1 million dollar raises for its school bus contractors, with the goal of increasing driver pay. Those increases ended this school year.

But Knox County doesn’t employ drivers directly. County school officials don’t know how many bus contractors passed the increases on to drivers.

Dillingham said he’s confident the district is now competitive with its neighbors, partly because of the contract increases but also because of better infrastructure, like a powerful radio system that provides support to drivers on far-flung routes.

Offering better pay, benefits, or hours are ways school districts entice and keep good drivers. But using contractors means Knox County doesn’t control these factors.

It’s been this way since the school district was created. Many of its contractors are mom ‘n’ pop businesses with a handful of buses. Contracts aren’t bid out, said Russ Oaks, chief operations officer for the school district. The school board approves a new contract that outlines a flat fee for each bus: Between about $41,000 and $48,000, depending on bus size. The contract is used for five years with all interested companies that meet the district’s standards.

Right now, there are about 60 contractors running 345 buses. Although that’s about half as many as contractors as five years ago, it’s way more than most large school districts in the state use. Memphis and Chattanooga public schools each use a single national contractor for school busing, for example. Memphis, at least, isn’t having a driver shortage: WATN reported this fall that the district had 60 more drivers than routes.

Nashville handles most of its bus transportation in-house. It guarantees drivers an eight-hour day, overtime and attendance bonuses. It is among the 64 percent of districts that handle their own bus transportation, according to School Bus Fleet.

After a head-on collision between two school buses killed2 children and an adult five years ago, the Knox County school board and top administration revamped bus driver training and safety requirements in addition to boosting pay. The district is considering taking over all driver training, Oaks says. It already runs background checks on drivers. Many don’t make it through the training and certification process; Oaks says about 200 new people wanted to drive this year but only 75 made the cut.

Still, amid all these changes, the district never reconsidered the broader structure of how school bus service is provided.

Oaks says he andKCS transportation director Ryan Dillingham revisit the question frequently. “We’ve not got to anything that tells us we can do it better and more effectively for equal or less money,” Oaks says.

This year, Knox County Schools budgeted 21.7-million dollars for school bus transportation. The state reimburses $8 million of that. State reimbursements seem to be climbing along with local expenditures.

It’s often assumed that using contractors is cheaper. This year, the Keystone Research Center published a study that found the opposite to be true in Pennsylvania, where the policy institute is based.

Buying and maintaining a bus fleet would cost a lot up front. And employing 400 drivers would create extra management expense, Oaks says.

Taking busing out of contractors’ handscould backfire in some ways, says school board member Kristi Kristy. “I’m not sure that if we did our transportation in-house if it would help us with the driver shortage,” she said.

That’s because many drivers enjoy working for their family business. It’s one of the advantages of the current system, as Dillingham sees it.

“These contractors and these drivers are stitched into the fabric of our community,” he said. For example: “Bus 1 is run by the same contractor whose great-grandfather started Bus 1. Generations of people have grown up knowing who is going to be running their bus, and that story is retold across the county.”

In the past, school board policy limited the routes any one contractor could take, which protected these small operations and kept the number of contractors high. In recent years, the district has deliberately tried to reduce the number. With fewer contractors, it’s easier to communicate and maintain consistency, Oaks said. Plus, contractors with more buses have more flexibility to cover a route when something goes wrong.

Even so, there’s not a single contractor that comes close to handling even a fifth of the routes, he said.

The school district bus contracts mention performance generally but don’t include specific requirements, like an on-time rate or a deadline for filling empty drivers’ seats, Oaks said. It looks at problems on a case-by-case basis.

“At some point you’ll get to the point where you’re not fulfilling your contractual obligations, and we’ll start looking at do we need to take routes from you or do we need to terminate your contract,” Oaks said.

But Kristy says she rarely hears complaints about bus service. “I’d be willing to look at it if there are better ways for us to do things,” she said, but, “I do think we do a good job with transportation.”

Even so, Oaks sees the driver shortage as likely to persist, giving drivers leverage to ask for more money or leave.

The district’s biggest contractor, EcoRide, stopped working in Knox County this year, saying the contract wasn’t profitable for the company.

Oakes said future budgets may include regular increases for bus contracts to keep the district competitive.

Kristy said she’d be open to supporting that, especially if it helps keep kids safer on the bus. She also suggested that future contracts could include more detailed requirements, such as a minimum driver salary.

But Oaks said the district has been reluctant to get too specific in the contracts. “The challenge for us is: If we have 60 contractors, they’ve probably got 60 different business models,” he said. “And if we try to insert ourselves too significantly into somebody’s business model, we may be creating a problem or unintended consequences that we did not see.”